Most likely through imported innovation.

Simon Johnson asks the question rhetorically while explaining growth is the product of labour (quantity and quality), capital, technology – and the residual, or total factor productivity or the way these factors are organised.

Technology has a significant role as the most recent Nobel laureate on Econoics Paul Romer explains. Romer’s theory describes firms’ choice between investing in innovation and production, accepting the returns on innovation are seldom fully internalised by firms whilst being significantly higher than those of ordinary production.

As the opportunity-cost of production in this two-occupation model is significant, revenues in foreign firms located in fast-growing economies typically grow much faster than costs – at least until such costs increase so as to decrease the opportunity-cost of production.

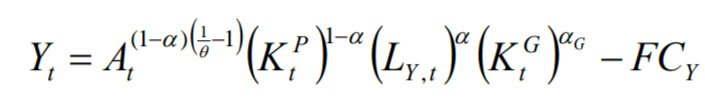

At a macro level, capital, labour and technology are joined by government spending (K g on the equation below) and fixed costs (FC) such that institutions (that adequately allocate public capital investment) and supply shocks (foreign or domestic) matter to firm output. Notice the model is succint yet more encompassing than Johnson’s description.

Different factor intensities deliver growth at different paces. Fast-growing countries present specific characteristics explored in the coming posts focusing topics such as unconditional convergence, the role of government and foreign content of exports.

One thought on “How are countries converging?”